The Wizard and I: Sharing My Experience of Prototype Testing Using Wizard of Oz

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and his animatronic head • Image credit to the Wicked movie and Universal Studios.

Introduction

Wicked: For Good movie is finally here! As a former theatre kid and longtime Wicked-TWWOZ fan, I thought it would be a great time to discuss a design method named after the infamous character: The Wizard of Oz.

This is a prototyping method that I often used back when studying interaction design, especially when we were building physical and extended reality projects. This method matters for many design teams today in order to physicalise their ideas to their team or stakeholders without having to spend a good amount of time to actually build and code it.

In this article, I am going to share about what the Wizard of Oz method is, when to use it, and the benefits, as well as an example from my own project.

What is Wizard of Oz Testing?

In the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz, Dorothy and her friends must travel to the Emerald City to seek help from the Wizard of Oz so she can return home to Kansas. The wizard was believed to be the most powerful in the entire kingdom, able to grant any wish. However, in reality, he was just a conman from Earth who deceived the Ozians by pretending he could read the grimmorie and create magic to have control over the kingdom.

After gaining influence in Oz, he created a false persona by projecting himself using a giant animatronic head with all sorts of effects like smoke and flames. His goal was to project an image of omnipotence and instil fear, which prevented anyone from realising he was just a small, ordinary man.

He was not doing any actual magic. The wizard was pulling strings behind the curtain and using all sorts of tricks and illusions. This is where the idea of the prototyping method came from.

The Wizard of Oz’s animatronic head is used to communicate with the citizen of Oz • Image credit to the Wicked movie and Universal Studios.

The Wizard of Oz method works like this: you create a low-fidelity prototype and invite users to interact with it. Users perform actions and receive responses (i.e., tapping buttons, asking questions, triggering notifications), but here's the trick: those responses aren't generated by actual technology. Instead, the design team is behind the scenes, manually controlling everything to make it feel real. The user sees magic; you're pulling the strings behind the curtain.

Here are two examples showing how this works. Let's say you want to test a voice assistant feature in your app before building any speech recognition technology. Users speak commands into their phone while someone from your team sits in another room, listening through headphones and manually triggering the responses (i.e., playing audio, showing search results, or opening features). To the user, they're talking to AI. In reality, it's just a person responding in real time.

Now for a physical example: imagine testing a smart planter that automatically waters plants based on soil moisture. You build a prototype with sensors and lights, but instead of coding complex algorithms, someone on your team just watches the plant and manually activates the watering when needed. Users see an intelligent device doing its thing, not knowing there's a human making those calls behind the scenes.

When to Use Wizard of Oz

The Wizard of Oz method can be useful to test brand-new concepts, expensive-to-build features or products, and complex interactions. For instance, my team once designed a concept for UQ Sports Centre to improve its experience and accessibility using technology. Once the formative research was done, we manifested the chosen idea into a physical object. But the idea does not stop only at the visual; rather, we also have to evaluate how users eventually interact with the idea.

Of course we cannot build a real sports centre just to test the interactions. It’ll be very costly, both time- and expense-wise. This is where the Wizard of Oz method comes in handy.

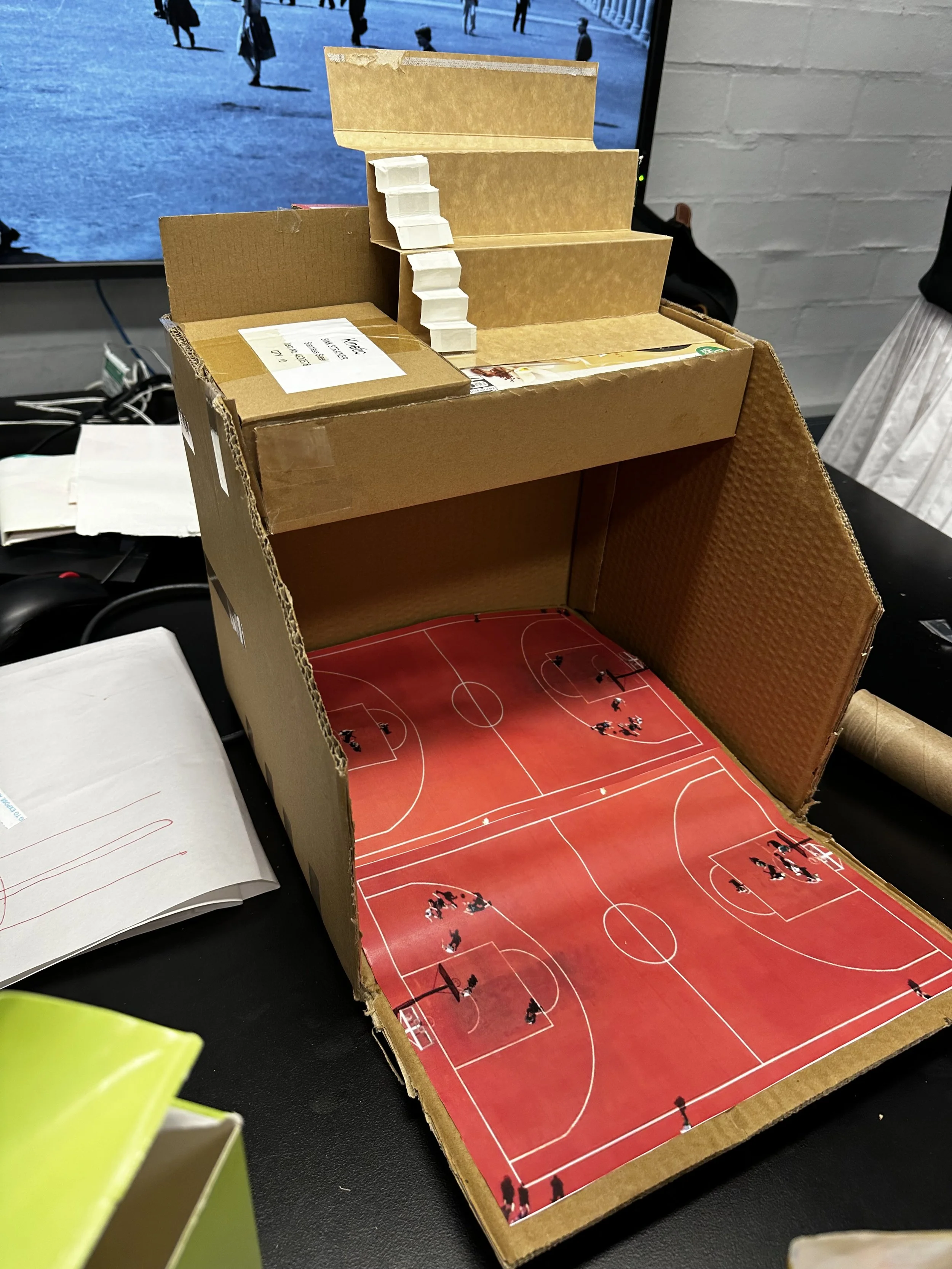

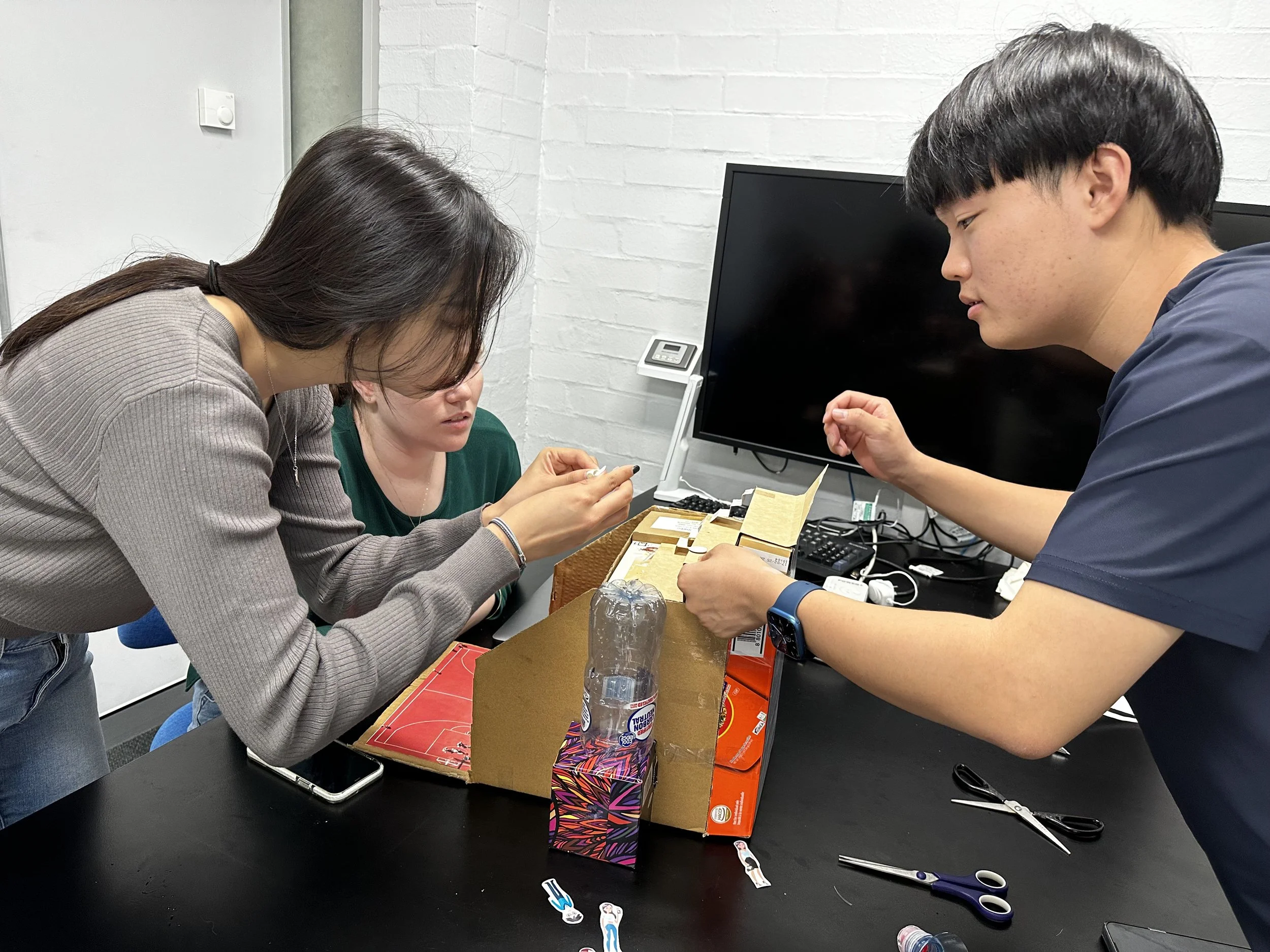

Using cardboards, used bottles, and other scraps, we built the miniature of the UQ Sports Centre’s indoor centre and embedded some tricks inside of it. Then, we gave our users a task scenario which they needed to figure out how to do themselves. Our team took notes, like whether they were able to achieve the goal or not, how they did it, and what issues/undesired paths occurred. We learned about how users perceive the design and listed down what was good or had room for improvement.

This method, however in my personal opinion, is not ideal to use for testing simple design changes or well-established patterns. I think this method works better for complex, untested ideas – concepts that nobody in the team would know whether it’d work or not – and I don’t think it’s suitable for testing a simple UI change.

It is also not suitable when you need to gather performance data from the testing because you can’t put analytics in it.

It could be useful, though, for testing conversational AI, as you are testing more than just the design of the screen but also the flow of the conversation, how to generate responses, and so on. For example, if you are testing an AI chatbot with users, their input can be very random and unexpected. If we want to test the natural experience, instead of bringing pre-made questions or answers to choose, we can set a team member as the “wizard” that controls the interface and create responses based on whatever the user asks.

Benefits for the Design Team

Validate concepts before engineering investment: Test if users even want/understand the feature

Faster iteration cycles: Change the "magic" behind curtain without rebuilding

Uncover edge cases early: See how users actually behave vs. how you predicted

Build stakeholder confidence: Show working "prototype" to get buy-in for development

Bridge designer-engineer communication: Clarify requirements by seeing what users actually need

Practical Tips for Running Wizard of Oz Tests

Planning

First, decide on the interactive part of the prototype. Ask ourselves, “what can the product do, and how do users interact with that?” For instance, maybe a button to turn on the machine or a voice command that activates with a certain keyword.

Second, plan on what kind of responses users will get afterwards. It has to be meaningful and provide clarity towards the state the machine currently is in. For example, if the user clicked on the power button, we could play a tune that indicates that the machine has successfully powered on.

Lastly, coordinate the “performance” with the design team. Decide who becomes the “wizard(s)” to operate the prototype, who’ll take notes to capture insights, and who’ll be the spokesperson.

Execution

Sometimes, our prototype uses only a small portion of the technology (for example, using Arduino to build a controller) and is not fully complete. In such cases, we need to manage manual tasks and handle unexpected user actions or errors.

Ethics

According to NNGroup, we don’t really need to disclose it to the users to ensure authentic and natural responses to the prototype. But you may inform them that the testing itself is using a low-fidelity form, so it may not have a visual of a production-level object. After the testing session ends, you may inform them the truth about the procedure, in which they can choose whether they still want to be part of the data or not.

How To Conduct One

I will not reinvent the wheel; go check out the article from Interaction Design Foundation about Wizard of Oz Prototype here.

My Past Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Not anticipating errors

My Arduino suddenly stopped working in the middle of the test, and I did not prepare a plan to mitigate it, which caused confusion in the user as to whether this was their fault or not. Another case was when the user did an unexpected input that we did not prepare for as well.

How to avoid them:

While sudden errors from technology can be random and outside our control, we could mitigate them by really making sure the code and wiring work by trying the prototype internally several times.

Also work with the team to create possible scenarios that users might do. Try role-playing as a variety of people – a mischievous kid, an elderly person, or people with disabilities – as it can be a great start to becoming more aware and prepared for such cases.

Not all team member read and follow the testing manual

At one time, a member that usually did the testing was unavailable, which caused the testing procedure to be skewed from the plan. When testing a prototype, it is important that the same procedure is done to every participant to avoid inconsistencies in data collection, which can lead to unreliable results. Variations in how tests are conducted can introduce bias, affect the participant’s experience, and ultimately compromise the validity and comparability of the findings.

How to avoid them:

The ‘wizard’ can be tired from long testing sessions with intense focus towards users’ actions. Every team member has to understand the testing manual so that they can fill in a role when the ‘wizard’ or other roles are unavailable.

Having a written document that is accessible to everyone in the team is important so they can read it and follow along during the session.

Not creating spare parts in case of the prototype breaking

We lost some part in our design because somebody thought it was trash (which actually, we did build the prototype using scraps and trash). Sadly, we did not prepare a spare part, so we need to procure another material and recreate it.

How to avoid them:

Label your prototype so people (i.e., the kind cleaning lady) won’t mistake it for trash and throw it away.

Always have extra materials, especially the ones that hard to get or make.

Conclusion

Wizard of Oz is about learning efficiently: This method lets you test ambitious ideas without spending engineering resources or waiting months for a working prototype.

Perfect for uncertain concepts: When you have an idea that's too complex to sketch but too risky to build, Wizard of Oz gives you real user feedback quickly.

Focus on insights, not perfection: Your prototype can be scrappy as long as users can interact with it naturally and you're capturing meaningful data about their behavior.

Prepare for things to go wrong: The biggest mistakes aren't about prototypes breaking. They're about not being ready when they do. Test your setup, create spares, and make sure everyone knows the plan.

Manual testing creates real value: Some of the most valuable insights come from watching users interact with "fake" features because you're testing the concept itself, not the technology.

Try it on your next project: Next time you're wondering "should we build this?" or "will users even want this?", grab some materials, recruit a teammate to play wizard, and find out before writing any code.

Final thought: Like the Wizard who eventually revealed himself and still helped Dorothy, your manual prototype is just a tool. What matters is learning what your users actually need.

Cheers,

Desi Umpuan