Designing For Context: How Location, Situation, and Users Affect Design

How might we design a playground in an urban neighbourhood in Australia for kids under 10?

Introduction

During the making of one assignment for the Design Thinking class, I made a mistake that pushed back two weeks of work back to square one. We were told to observe a communal place where many people gather and do activities – think like a park or a gym – then identify the problems and potential solutions for them.

I decided to observe a BBQ place near my university’s student union area. Took some notes, sketches, and stuff. When the teaching assistant asked us to identify a problem, I misunderstood the brief and decided to mistakenly investigate:

(1) “What are the problems that university students face about cooking?”

Instead of asking a question specific to the context I have chosen:

(2) “What are the problems in that UQ Union’s BBQ place?”

The difference between these two guiding questions lies in their scope: the second is context-specific, focused on a particular location, activities, and users. Investigating a design problem within a defined context—such as cooking at the UQ Union’s BBQ area—leads to distinct research goals and outcomes compared to a broader, more general inquiry like the first question.

There’s no right or wrong, or better or worse. It depends on the design goal: are we designing for a specific place, like a ticketing lobby or a dorm common area? Or do we want to explore a theme from a broad view?

During real-life work, however, we are often required to pay attention to the context of where the technology (i.e., mobile apps) is intended for. It can be contextually based on the region and the specific wants-needs that region has.

Let’s take Shopee as an example. In Southeast Asia, this marketplace giant is the most popular app for online shopping, even more than Amazon. Although the core platform is the same, the Indonesian version is quite different from the Singapore one. Many features and the user interface are tailored to meet the specific needs of Indonesian shoppers, making it uniquely suited to their context.

This shows that the same app works differently depending on the situation. To create user-focused products, understanding the context is essential.

So, What is Context in Design?

According to the Interaction Design Foundation, contextual design recognises that no design exists in isolation. Each technology or system interacts within a broader, changing environment. Therefore, it aims to place designs within their context to enhance their effectiveness [1]. In contextual design, there’s a term called “work practice”, which means the detailed and complex ways users behave, think, and aim when working in a specific setting [2].

To put it simply, designing for context means creating a product or experience that is tailored to the specific location, users, and situation in which it will be used.

For example, imagine we were tasked to design an experience for a community centre. We need to take into account context-specific questions, such as:

Location: Where is it built? What country or region? What does the neighbourhood look like?

Users: Who are the people who will come and do activities here? What are their roles? What age group?

Situation: What kind of activities are people doing? When usually people go here? What local sports do people like?

We need to understand these three pillars before designing our community centre because they help us grasp the environment and how people interact within it. Considering local culture and habits is essential, as a community centre in, let’s say, Indonesia will likely differ from one in Singapore. So, it is important to understand the challenge based on its own context, not by applying foreign ideas.

Location: Where Users Are

"When in Rome, do as the Romans do" – an old proverb taught us to observe, adapt, and follow the local customs we are on. When designing a user experience, it is important to do the same in order to create an experience that is tailored to the locals.

Observing the location can help us gather non-verbal information about the environment and understand their problems and needs, which we couldn’t find out otherwise.

We could take a look at the physical environment: is it indoor or outdoor, the lighting, noise, etc.

We could also look at the geographic and cultural factors: the terrain, climate, culture, beliefs, etc.

For example, the hawker centre culture is unique to Singapore. The rules, the stalls, the colouring of the trays – they are tailored to Singaporeans and their culture. However, this won’t easily work the same if we copy-paste it directly to any other countries. Some adjustments and localisation towards the region’s physical environment, geographic, and cultural factors have to come into place when designing the experience.

In a park, people from all age groups doing various kind of activity such as yoga, reading a book, picnic, or playing catch with their pets.

On websites and mobile apps, location influences how information is presented. For example, Arabic readers read text from right to left, while in Japan, some media display text vertically. Additionally, cultural meanings of colours vary: red symbolises luck in many Asian cultures but can indicate danger in Western cultures. Understanding these nuances is essential when designing for specific regions.

Some great resources to read:

Innovating or Imitating? The Interplay of Western and Asian Digital Product Design – By Jo Chang on UXmatters

Chinese app design: weird, but it works. Here's why – By Phoebe Yu

Situation: What Users Are Doing

'Situation' refers to the social and physical condition of the surroundings. It can be about the activities or practices happening in the vicinity, the timing or urgency, and the devices or platforms being used.

Let's say we were tasked with designing a better queuing experience for an airport's check-in process to not only make the waiting time enjoyable but also reduce the length of the lines. We could start by understanding the 'work practices' of the context through field observations in the natural environment and ask them questions.

Consider the urgency of various guests and their luggage. What about those who bring kids or elderly? How was their psychological state? What if the kids started to cry or bored?

Queuing for check-in at the airport can be more hectic and crowded during holiday seasons.

In mobile app design, 'situation' refers to the events or circumstances that prompt users to open and interact with the app. This concept extends beyond the on-screen content to encompass the user's physical and social environment, such as being in a busy store compared to a quiet home office.

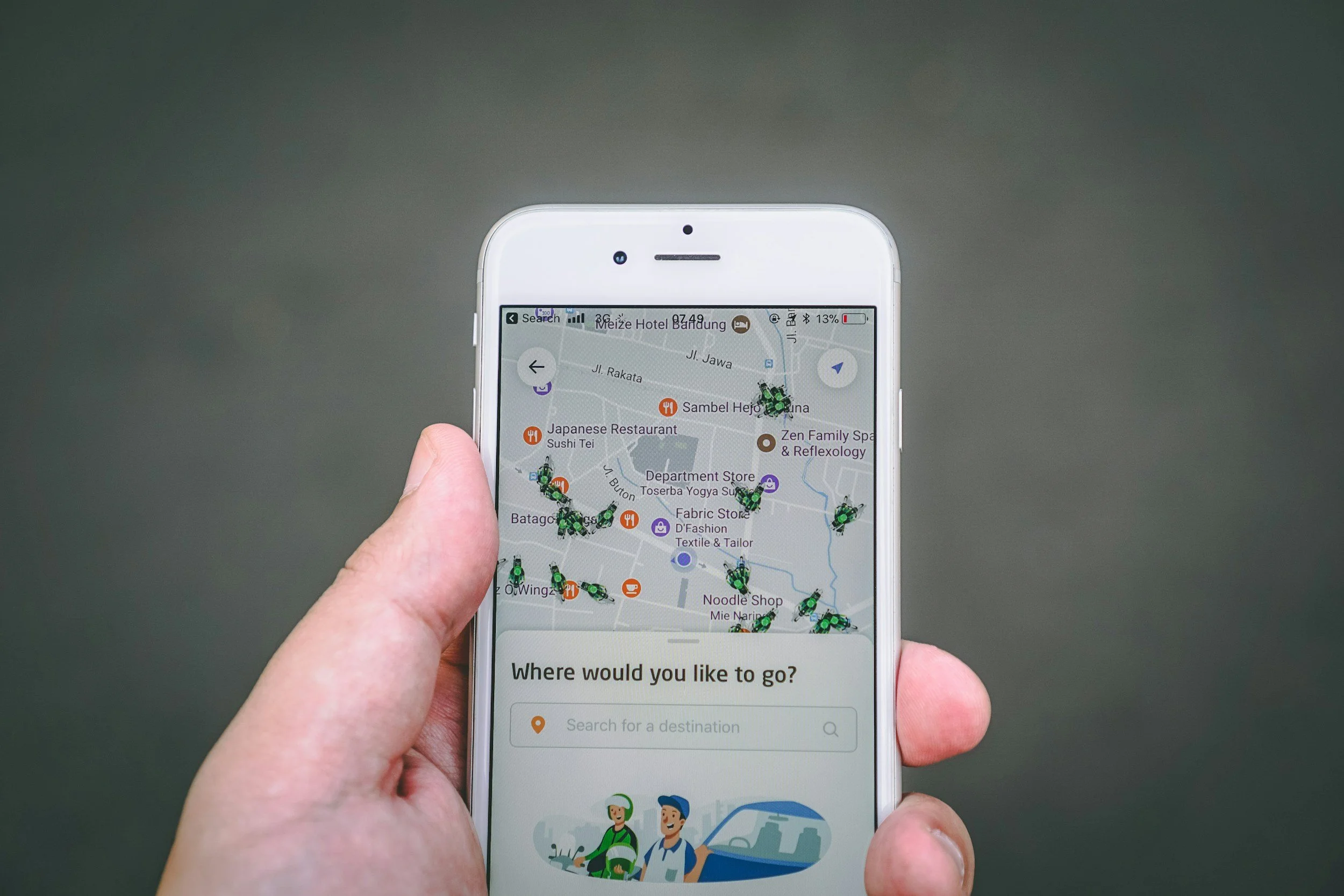

When designing a ride-hailing app, it is very important to understand the situational context of its usage. From where I came from in Jakarta, motorcycle taxis, also known as 'ojek online', are an integral part of people's daily commute. People often ordered their ride even when they're still on the train or walking inside the station, which is often crowded and noisy, with little space to move around.

Situational awareness of this instance has allowed many useful features that helped both the passenger and the driver, such as shortcuts for regular users, auto-detecting the nearest possible pickup point, chat instead of calls, and text templates consisting of common phrases used between the two roles.

Indonesian ride-hailing app, Gojek

It is also affecting the design style of the user interface, which has a clean and minimalistic design with a controlled amount of information being shown, such as less intrusive banners and advertisements that won't overshadow the important elements, allowing faster and accurate navigation during such a hectic time.

These features would allow users to navigate their surroundings and achieve their goal (i.e., booking a ride).

In contrast, an investment app I designed operates in a completely different situational context. Unlike the ride-hailing app used in crowded, time-sensitive environments, financial apps are typically opened in calmer, more private settings—at home on the sofa or during a quiet moment at the office.

This situational difference allowed me to design more information-dense screens that users could carefully review and analyse. While this doesn't justify cluttering the interface with unorganised data, it does permit a more complex layout where multiple data points, charts, and detailed financial information can coexist. The lack of urgency and distraction in these usage scenarios means users have the cognitive bandwidth to process layered information that would be overwhelming in high-pressure contexts.

An example of an investment app, which often are information-dense with a lot of graphics

Users: Who They Are

A good system understands its users. It simply means that the system is created to resonate and support the people using it, not disrupting nor forcing them to learn a completely new way of doing things. Even when we're designing a disruptive form, we could still think about how it seamlessly blends into the environment and reduces the learning curve.

One important note to highlight is that what works for users in other places might not work for the folks in here. I often saw some government officials back in Indonesia trying to impose rules or measures from the capital and was shocked it did not work as well in, let's say, a more rural region. Even though the core objective is the same, the way it's going to be implemented can always be adjusted towards the target.

We discussed location and situation. Even in the same place and situation, different users exist. Understanding their goals, problems, and needs can be a good start to research and improve the environment to make their tasks easier.

Let's take supermarket shoppers as an example. We knew that people of all ages, demographics, psychographics, and varying levels of accessibility regularly came here to shop. This diverse group included families, singles, seniors, and everyone in between, each with their own unique needs and preferences.

By understanding this, we could improve the experience of many areas, such as navigation and findability.

Or if there's a specific business need to improve – like reducing checkout lines or making people interested in buying a certain product – things would be easier for the team to ideate when they knew how every user group or persona would behave.

Conclusion

Context is not optional: Understanding location, situation, and users isn't just a nice-to-have—it's fundamental to creating designs that actually work in the real world and solve real problems for real people.

Reflect on the BBQ place mistake: Circle back to the opening story—that two-week setback taught you that context-specific design questions lead to more actionable, meaningful solutions than generic ones.

Context shapes everything: From the minimalist UI of a ride-hailing app used in crowded stations to the information-dense screens of an investment app used at home, context determines what "good design" actually means.

Avoid one-size-fits-all thinking: What works in Singapore won't necessarily work in Indonesia, and what works for one user group may fail for another—even in the same location.

Start with observation: Before jumping to solutions, spend time understanding the physical environment, cultural nuances, user behaviours, and situational constraints of your specific context.

Call to action: Next time you start a design project, ask yourself: Where will this be used? Who will use it? What situation will they be in? Let these questions guide your research and design decisions.

Final thought: Great design doesn't exist in a vacuum—it exists in the messy, complex, beautiful reality of human life. Design for that reality, not an idealised version of it.

Cheers,

Desi Umpuan

References

[1] Holtzblatt, K. and Beyer, H. R. (2014, January 1). Contextual Design. IxDF - Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/contextual-design

[2] IxDF - Interaction Design Foundation. (2015, August 3). The Key Principles of Contextual Design. IxDF - Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/article/the-key-principles-of-contextual-design